As the artist uses his thumb to press the line beside the figure’s mouth, a wrinkle gradually appears. Tap, tap, tap, and then comes the unevenness of the skin. Wen-ti Tsen uses his hands to breathe life into a lump of clay, transforming it into a laundry worker from the mid-19th century.

“I’m not satisfied with his head yet; it should not look happy nor miserable,” Tsen says, continuing to tap the clay head that looks back at him.

With his hunchback and buck teeth, the laundry worker’s awkward expression suggests he’s on the verge of saying something, yet decides to swallow it back. “His teeth are not very healthy, as his earnings don’t allow him to see a usually expensive dentist,” Tsen explains. The worker also wears slippers, as he has just walked from his living room to the counter, just steps away. Tsen brings the clay into a real life-size statue, not just in shape but also in the person’s life, thoughts, and essence.

As an artist who grew up in many cities, including Shanghai, Paris, and London, his style is dominated by Western culture. But this recent project he is working on is paying tribute to his origins: a Chinatown worker statue.

In the early stage of his work, he makes the first statue, the laundry man, at the Pao Arts Center in Chinatown for visitors to see his progress. “I like working here although I need to commute. Talking with people makes me energetic,” Tsen said, after some visitors stopped by his statue and asked him questions.

He moves with agility, climbing up and down the ladder, skillfully twisting the iron rod to add the finishing touches to the statue. “You are 88 years old!?” some visitors exclaimed while Tsen introduced his age. As an atypical 88-year-old, he still drives to work, from Pao Art Center from Cambridge, visits friends, sees exhibitions. In my second visit, he asked me some tips for Premiere, a video editing software by Adobe. I wasn’t surprised because he said he set up his personal website when we first met.

Wen-ti Tsen’s story begins in Shanghai, China, in 1936, amidst the turmoil of the Japanese invasion and subsequent conflicts. His early years were spent in the shadow of war, receiving his education at home until the post-World War II era allowed for a return to public schooling. Despite the turbulence of those times, Tsen’s family was relatively well-off.

The seed of Tsen’s artistry was planted by his mother, Fan Tchunpi, who had honed her skills in Western painting while living in France. Tsen recalls, “My childhood was filled with art books my mother brought home, depicting saints with arrows, naked goddesses, and winged horses.”

The Tsen family’s affluent lifestyle was largely due to his father’s close ties with the government, particularly with Wang Jingwei, who was known for heading the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China, a puppet state under Japan.

The family’s fortunes took a drastic turn in 1937 when Japan invaded China. The Tsens were forced to relocate to Chongqing along with the evacuated government. The government splits with Chiang Kai-Shek opposing Wang Jingwei, who had considered a peace offer from Japan. Wang eventually resigned as president and retreated to Hanoi, in French colonial Indochina, along with his supporters, including Tsen’s father.

During Tsen’s mother visiting her husband in Hanoi, Wang once offered them the use of his villa’s master bedroom, without knowing that the Chongqing government had been surveilling the villa. At that night, an assassination team dispatched, killed the man who slept in the master bedroom. And Yes, that wasn’t Wang. At that time, Tsen was only three years old.

After that accident, Tsen still lived in Shanghai while his mother was in recover from gun wound and sorrow. Eventually, they moved to Hong Kong and then to France to escape from the turnoil which created by newly emerged communist party. “Actually I was quite happy to be a refugee to go to France as I didn’t do well in elementary school.” Tsen said

Tsen eventually moved to London for high school and then studied architecture and art in Europe. In 1958, he came to America and studied painting at the Boston Museum School. At just 22 years old, Tsen had already lived in four different countries, not for leisure, but as a consequence of turmoil.

Compared to Tsen, the laundry worker came to the United States when he was likely over 30 years old, during an influx of Chinese immigrants surging to the United States because of the California Gold Rush. When the Gold Rush faded and the demand for labor waned, many Chinese immigrants faced unemployment and discrimination. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a federal law that prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States, made the situation worse.

Finding a job in the United States during this period became extremely difficult for Chinese individuals due to widespread discrimination, legal restrictions, and social hostility. Many Chinese immigrants who were already in the United States before the act were forced into low-paying, labor-intensive jobs, such as laundry work, domestic service, and manual labor.

Tsen’s four statue—a laundry man(currently working on), a cook, a female garment worker, and a grandmother taking care of her grandson, depicts those Chinese immigrant at that era. “Wen-ti’s helps second or younger generation Chinese immigrant to know how hard their predecessor’s life was,” says Christina Chan, a second-generation Chinese American playwright and a longtime friend of Tsen. She has been studying Asian American history for more than 30 years and is now writing a play about early Chinese immigrants.

This is Tsen’s first time working on a statue project but not first time in arts for public and social issue. On one tab of Tsen’s website, theres’ many posters he made: anti domestic violent, rights for immigrants.

“I don’t have my job anymore. My company’s folded. Everybody’s laid off. They just came out and told us today… like that. What are we to do?” a garment worker Chinese immigrant mother says. She’s a character in Tsen’s comic book, but also a reflection of most immigrants at that time. This quote, with grammatical inconsistency and stuttering, shows her struggle in English and her life in a foreign country.

This comic book sheds light on early Chinese immigrants life and struggle. Hard-working yet earning very little, their job stability and income could vanish in a single day. Tsen aims to infuse his works with message: giving readers a glimpse into the unimaginable hardships these people endured.

He spends over 10 hours in his studio, creating artwork, self-educating, and doing office work. Only a few things can drag him away from his work. “I will not go to the Pao Arts Center this week since it’s my wife’s birthday this weekend,” Tsen said. “We’re going to visit a museum.”

Visiting museums is their tradition, as is celebrating Shakespeare’s birthday.

It was April 23, 1963, when Tsen, then 27, young and established, had just started teaching. He held a party to celebrate Shakespeare’s birthday. A girl named Alice Evans attended with a friend and discovered a painting that was Tsen’s work. She initiated a conversation based on the painting, which marked the beginning of their 60-year relationship.

“As soon as I went to the party and saw this young man in the corner, I felt I needed to talk to him,” Alice laughed.

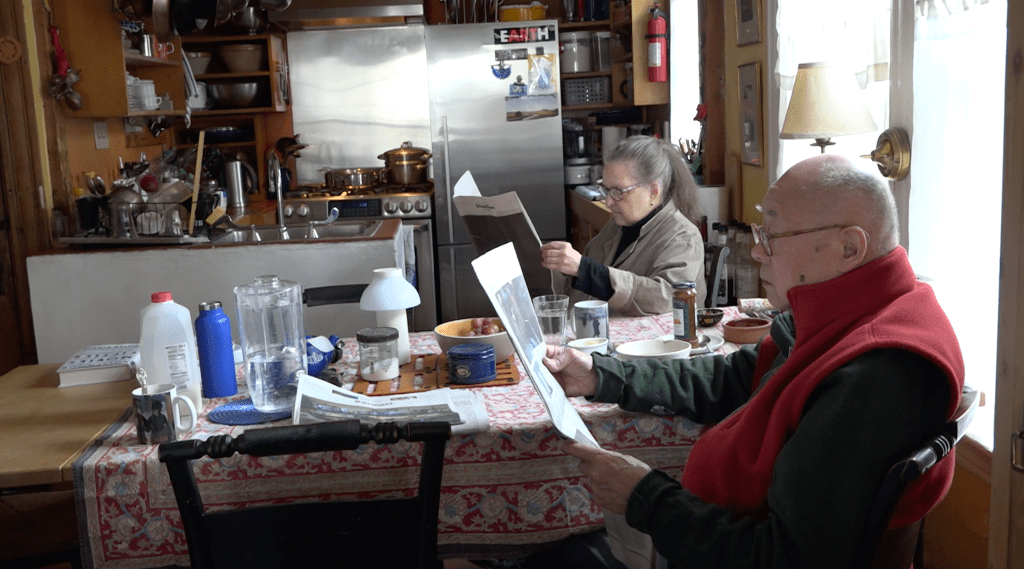

Every noon, Tsen sips his “morning coffee” from a bowl, a traditional old French style, while Alice makes herself lunch on the second floor of their house, a hangout space, as Alice calls it.

Their home perfectly illustrates their cooperation. The first floor is Tsen’s studio and room, as he is a night owl and needs a large space for working on statues and paintings. The third floor is Alice’s space, including her studio for making landscape designs, a skill she learned at 50. The second floor is their shared space for watching movies, having dinner, or simply catching up on their day.

“I think that’s part of the reason why we work well. He and I have our own independent spaces to calm ourselves down and engage in our own work,” Alice said.

Now, aside from the statue, Tsen is also working on a painting of his family members, a scene where his two daughters and grandchildren sit together in the living room. That’s what anchors him.

“Appreciate what surrounded me and accept the flow of life, that’s what I have learned from Dao De Jing” Tsen said.

The Dao De Jing is a cornerstone of Chinese Daoism and Taoism, offering a deep philosophical exploration of the concept of the “Dao” (the Way). It presents a comprehensive philosophical framework that extends from the governance of emperors to the personal cultivation of hermits.

Those who align with the Dao are believed to achieve a state of oneness with it, allowing them to act naturally and effortlessly in accordance with its principles. This is the essence of “wu-wei,” a concept often misunderstood as inaction but more accurately described as acting in harmony with the Dao.

“I’m applying ‘wu-wei’ in my life, focusing on the now and flowing with the currents with life.” Tsen said with calm voice while he looking at his statue, which is also looking back at him.

Leave a comment